View the Full Publication

(Click the image to read the full issue.)

Helping Future Forests Flourish

This year’s winter and spring has helped me more viscerally grasp the huge changes afoot for California and the world. Warmer temperatures and episodic precipitation are emerging as the “new normal.” In Earth’s ancient geological record, we have only hints of the many awesome changes our planet has experienced. Human civilization is but a brief entry in that record, during a relatively calm and stable period that could be coming to an end. Even the greatest natural challenges we’ve survived over the last 20,000 years occurred with far fewer of us, not yet dependent on the vast engineering of modern life. To paraphrase the famous Bette Davis line: Fasten your seat belts, we’re in for a bumpy ride.

Forests have played a central role in shaping the Earth and human welfare, beginning as a major source of life-giving atmospheric oxygen. Today, the contributions of forests to a livable planet are as compelling and crucial as ever: soaking up and storing dangerous levels of carbon dioxide pollution; filtering and metering out precious fresh water captured from rain and snow; and providing sheltering canopy and climate friendly building materials.

We have evolved with and benefited from forests over millennia. Forests are resilient, and by their nature, take the long view of things. People, too, are flexible and resilient. As the world’s scientists urgently alert us to the accelerated pace and scope of climate change, it is clear that forests and people need each other more than ever. With skillful stewardship and strategic investments we can help forests continue to flourish. We can and must conserve our forests from being broken up and developed. We can and must manage them to increase carbon sequestration, reduce catastrophic fire, and enhance water security.

We need human ingenuity and commitment to sustain the forests that sustain the world as we know it. With your support, PFT (with seatbelts fastened) is reinvesting in our commitment. Together we can leverage our 20 years of accomplishments to meet today’s urgent challenge of securing forest resiliency to benefit people everywhere.

Connie Best

It’s hot and dusty at midday when the cows start to drag their feet. Driven before daybreak from their valley floor home, the lead cows find a new sense of urgency as Alex counts them in the gate and cowboys encourage them up the last steep climb. Cresting the ridge, the cows prick up their ears, summon their calves, and begin to trot. The great meadow—a lush expanse in an alpine valley rimmed with rich forests—is still a mile below, but they can smell the cool mountain water on the breeze. “Blair’s Girls” race home again for the summer.

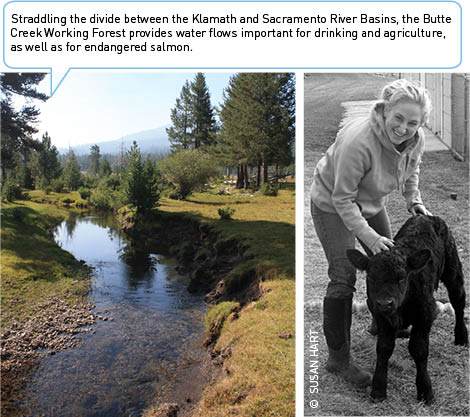

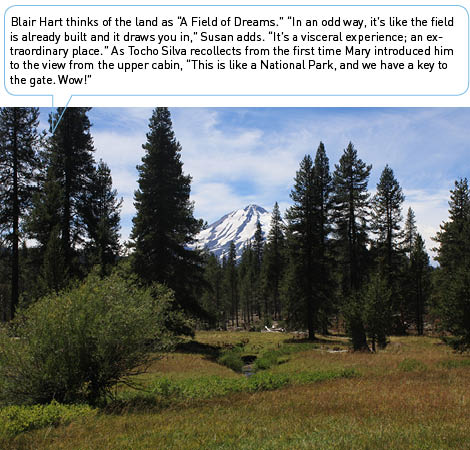

“It’s like going from black and white to color,” says Susan Hart of the first sight of Butte Creek Ranch from above. “I’ve never seen the sky so blue and the trees so green.” Married to Blair Hart, Susan’s been around the ranch for 33 years—a newcomer. And, like every member of the Hart family, she cut her teeth on the cattle drive; the 153rd drive starts this July. The family’s ancestor and avid hiker, John Miller, thought he’d found paradise when he happened upon this stunning landscape in the 1850s. The meadow, fed by springs that form the headwaters of Butte Creek, stays green well into August, and is still the perfect summer range; the forests are still bountiful and teeming with wildlife.

Five generations on, the Hart cousins and their families steward Butte Creek Ranch’s 3,145 acres with John Miller’s same sense of wonder—and a deep sense of responsibility. This place makes them feel as gleeful as kids. The meadow, dramatic rock cliffs, and the many high mountain glades—cousin Mary’s secret fairy gardens—sustain their spirits with peacefulness and solitude. It is now up to cousins Blair, Laura, Pam, Mary, their spouses, and their children, Jasmine and Alex, to maintain Butte Creek’s splendor. The family expresses, “After 160 years, we’re it. Being the stewards of the property is a tremendous privilege and responsibility. You want it to be this way forever.”

The Pacific Forest Trust is helping the family to do just that, by permanently conserving the ranch. The property embraces over 2,300 acres of well-managed high-elevation forest, 800 acres of high-quality wet meadow habitat, and almost four miles of the headwaters of Butte Creek, in the Klamath Basin near Mt. Shasta. A working forest conservation easement here will prevent the break up or development of the ranch, and support the family’s outstanding cattle and forest management. Protecting this land secures an important wildlife corridor that connects the Shasta-Trinity National Forest and the Klamath National Forest, and enhances habitat for imperiled species such as the northern spotted owl and the Pacific fisher.

California has lost most of its alpine wet meadows like those at Butte Creek, and the State recognizes their critical role for water supply as our climate changes. The easement will maintain and enhance these natural reservoirs that soak up winter snowmelt to release later in the summer when other sources have run dry.

The forests that surround these rich meadows will continue to be selectively managed for the long-term health of the property. The property’s mixed conifer stands have more natural complexity important for habitat—including mature stands with bigger, older trees—than are usually found on most privately owned forestland. Susan Hart explains, “We’ve been working to clean up the conifers and restore them to their historic qualities, and make the timber that’s there healthy, mitigating for disease, fire risk, and hazards. This is just the start of managing this property going forward.”

With its mosaic of vegetation types, rare habitat elements, and water resources, wildlife is abundant on Butte Creek Ranch. “We see raptors soaring over the valley all the time,” Mary and Tocho Silva report. “Falcons, eagles, goshawks. They love it here as much as we do.” An estimated 63 fish and wildlife species live here, like the Silver haired bat, prairie falcon, Sandhill crane, Cascades frog, and Oregon snowshoe hare.

A working forest conservation easement allows the family to sustain their cattle operations, which are third-party certified by the Global Animal Partnership for humane treatment of animals. Blair explains, “We want to provide only what we’d be willing to consume ourselves. Our cattle are grass fed, antibiotic and hormone free. Environmentally, we are dealing with a very limited resource: water. Sustainability, both in resources and operations, must be the new norm. We’ve made a tremendous investment in buying feed-efficient genetics to support the cattle side of the equation.”

Now the family is looking to the property’s future. “Where do we want to take the ranch? We know it’s very valuable for the environment and wildlife. How can we do all of this? We’re cattle people, we need forestry expertise. PFT has an extraordinary wealth of knowledge and expertise. We have learned more from our association with PFT and their network of resources in the last 18 months than we have in 30 years.”

Perhaps the Hart cousins’ determination comes from John Miller’s sister, Louisa Hart. In the 1850s, she journeyed by boat from New York, and rode a mule across the Isthmus of Panama carrying her two diaper-clad sons to make Hart Ranch and Butte Creek her home. She stewarded the land with tenacity until her passing at age 87. The family decided that permanently conserving their land was the best way to respect this heritage.

“We want Butte Creek Ranch to remain as it is and continue to improve it in perpetuity,” Susan remarks. “A conservation easement makes it financially possible for us to continue good stewardship. This is our contribution to California’s forests and wildlife. You do it because it’s the right thing to do.”

In California water debates, we always hear the same few solutions. Dams, more and higher dams, more and deeper wells, and desalinization lead the chorus. Beyond trying to squeeze more water out, we overlook taking care of the primary source of our water itself: our watersheds.

One of the simplest, cheapest and most effective things we could do to ensure greater water security and quantity is to restore and maintain our watersheds. By most estimates, this could increase supplies by anywhere from 5-20% depending on the watershed. That’s a big number. Even without an increase, restoring our watersheds improves our water supply’s reliability and quality.

Precious water, uncertain climate

Most of California’s water for drinking and agriculture comes from forested watersheds in the north state. Nine counties of the Klamath-Cascade region provide water to the mighty Sacramento River, which supplies 60% of irrigated agricultural water, drinking water to 25 million residents, and over 80% of the freshwater for San Francisco Bay. Within the global warming—and drying—gloom that models predict, there is a bright spot. “Areas that are the source of the Sacramento River, especially the Mt. Shasta Headwaters region, have remained cooler and wetter than the rest of the state, which has mostly warmed and dried over the past century,” Dr. Steven Beissinger reports in his research on how California’s plants and animals are responding to climate change. Keeping the watersheds of the Klamath-Cascade healthy and functioning is essential to California’s water supply.

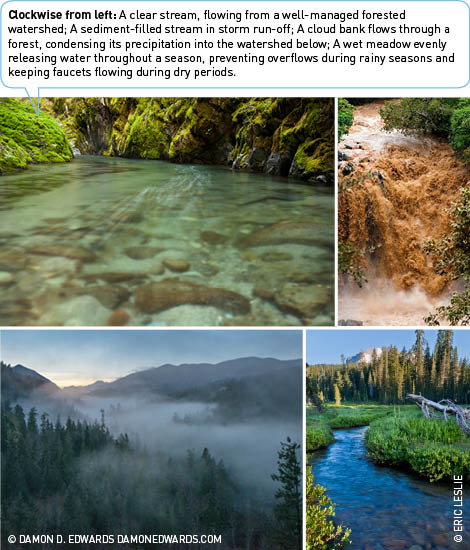

Natural watersheds keep water flowing

Maintaining our watersheds’ natural function means reducing development, and keeping forests intact. More natural, complex forest structures, with well developed canopies and deep tree crowns, are an important element of well-functioning watersheds. Dr. Jerry Franklin notes that, “In landscapes subjected to frequent fogs or low clouds, forests with well-developed canopies can condense large amounts of moisture and add significantly—20% or more—to the amount of precipitation reaching the ground.” Tall trees in our coastal and mountain watersheds create air turbulence, trapping cloud and fog moisture to collect on leaves and needles, which then precipitates out.

Covered and connected: watersheds need a mix of trees

According to climate scientist Dr. John Holdren, global warming will cause soils to dry out more rapidly, leading to shorter water seasons. A contiguous tree canopy provides shade that maintains soil moisture and snow cover longer, extending the water season. Forest canopy irregularity and spacing is important to allow snow to filter in more effectively, rather than having the even, impenetrable cover of same age and size trees that some forestry produces. A full canopy also helps intercept and diminish the impact of the increasingly frequent and intense downpours that global warming brings. With more of our precipitation in erratic episodes of extreme rain, catching and holding the water in our forests is essential to any water strategy.

Give trees some space and turn down the heat on wildfire

More natural open spacing allows fire to run along the forest floor, rather than racing through tightly packed trees and up them into a devastating crown fire. Those crown fires lead to enormous quantities of ash and then soil erosion, clogging waterways and dams. As the recent Rim Fire so dramatically illustrated and the USFS documented, more natural forests better tolerated the fire, while the younger, crowded plantations on both federal and private lands did not. More natural spacing means fewer trees to the acre. Fewer trees take up less water overall, but actually grow faster—a winning strategy for restoring taller trees, maintaining a more natural forest, and producing more water for streams.

The magic of meadows

In a natural forested watershed, meadow systems weave in and around forested hills and are an integral part of stream systems. Teeming with plants and wildlife, these emerald sponges collect, filter, and absorb water. They function best when surrounding forests are maintained within their historical boundaries, rather than encroaching in due to a lack of fire. When surrounding forests provide consistent cover, water filters in gradually, rather than flooding through. Flooding erodes stream channels, and creates a self-perpetuating problem: the more eroded stream is, the faster water flows through in an ever-worsening cycle.

You can lead an “expert” to water, but…

Even with such a clear path to—and payoff from—excellent watershed condition and function, this solution falls far short of the “top ten list” of things water pontificators are recommending to help end our “water crisis”. Whatever the reason for overlooking this vital source-water historically (we just take it for granted, it’s “too complicated”, it’s not my agency’s business) it’s time we turn our focus to basic source-water issues.

There is hope that the science of watershed function will make it into policy and management. Water managers are starting to pay attention to mountain meadows for their sponge-like functions, and recognizing the need to restore them. Next, water managers and policy makers must recognize that those amazing meadows function as part of a forest watershed system. The whole forest is the essential water collection, cleaning, storage, and delivery system—not just individual parts.

The natural watershed solution: what’s next?

So what needs to be done? How does that stack up with the costs of other measures that are proposed to help ensure current water supplies or increase them? First and foremost, we need to reduce development and fragmentation in our watersheds. This will improve overall watershed function, reduce fire intensity and erosion, and allow for landscape-scale management.

Next, we need to help both public and private landowners manage for more natural forest conditions. With federal lands, that means supporting efforts to reduce stocking of overly-dense young forests, building more social license for these programs to operate, and providing the funding for consistent, proactive restoration management.

For private owners, it means providing the funding to offset foregone development and paying for the time-value of longer rotations and managing for older, more natural forests. Conservation easements that limit development and guide forest management pay landowners for that value. Tradable development rights, county planning, and other long-term agreements like PTEIRs are also tools that help landowners manage for improved watershed function.

Managing the whole landscape: a great return on investment

What would it cost to restore and sustain the watershed of the Sacramento River? Just focusing on the water delivered via the Central Valley and State Water Projects (not including all the other water consumed along the way), the cost would be less than a penny a gallon. That is a small price for water security from the Sacramento River. The likely increase of a minimum of 5% of water supplied comes along for free! Add to that the benefit of reducing fire intensity (another savings of almost $2,000/acre), and one sees how much the water-consuming California public benefits by source-water protection.

Forest landscapes are like a fabric that has been cut into a collection of patchwork quilt pieces scattered across property boundaries of federal and various private owners. And, like a quilt that has been torn apart, it just does not work as well as if the quilt were sewn together. Investing in source watershed protection and restoration, combined with new tools to allow consistent management across property boundaries within watersheds, will enable our watersheds to produce more water to more Californians at a lower cost than any other single solution.

ADAPTIVE WATERSHED MANAGEMENT

Experts estimate that forest restoration, including the wet meadows within them, can both stabilize and increase water flows from watersheds from 5-20%. While each watershed differs, overall, a more natural structure that mimics the diverse, complex forest structure is key to restoring more natural water capture, storage, and release. Here are some of the approaches they suggest:

Keep Forests Continuous: Reduce fragmentation and maintain 85% cover; watershed function declines drastically if more than 10-20% of tree cover is lost.

Keep it Cool: Restore and maintain canopy cover over streams.

Keep it Clean: Reduce sediment; increase buffers and upslope retention; and decrease fire intensity through restoring more open natural structures.

Decrease Flooding: Reduce “rain-on-snow” events through increased shade. Slow melt increases water yields throughout the year as well.

Increase Summer Release: Retain big, dead down logs which hold moisture longer; thin the forest of dense, small tree stands; and retain winter snow and soil moisture longer through increased tall tree shade.

Increase Total Precipitation: Leave trees and groups of trees untouched to develop late seral characteristics. Large, tall trees capture more moisture from air, have lower transpiration demands, and allow deeper soil moisture than dense, young stands.

Chuck Leavell satisfies our curiosity

PFT’s 2014 Outside-the-Box honoree is one of the most accomplished keyboardists in rock music history, the sixth Rolling Stone, and a long-time member of the Allman Brothers Band, among many others. He’s also an honorary Forest Ranger, and an environmental and climate advocate. He owns and manages a 2,800-acre working forest in central Georgia with his wife, Rose Lane Leavell.

Q: How do you balance a Grammy-winning music career with life on the Charlane Plantation?

“These days, the Stones like to do relatively short runs of about six weeks. From there, I prioritize Charlane, The Mother Nature Network, and my own musical career. I get enough time at home to do most of the seasonal forestry work. We plant in the winter, and do prescribed burning starting around February and into mid-April. Wildlife management and restoration projects are in spring to midsummer.“

Q: What’s your favorite spot on Charlane? What do you enjoy most about your ranch?

“We have a 120-acre tract that we call the Tall Pines. Rose Lane’s grandparents had them planted back in the late ‘50s, so they are very mature and beautiful. I enjoy the physical work and the results it brings. But I’ll also quote Ralph Waldo Emerson: “In the woods we return to reason and faith.”

Q: What advice do you have for people who want to help solve our climate crisis?

“Little things add up. We can all help by living by the phrase renew, reuse, recycle. We can gradually turn our old energy guzzling appliances and vehicles to new energy efficient ones. We can all walk more and drive less. But on the large scale: Vote for leaders that want to do the right thing for our climate. Encourage incentives for things like conservation easements, biofuel usage, and solar and wind technologies. Encourage sound and sustainable forest management for both public and private forests. At The Mother Nature Network, we strive to give folks good, common sense ideas and answers to our environmental challenges. I believe that if people are well informed, they will make good choices that will lead to a better planet for all of us.”

You can learn more about Chuck at www.chuckleavell.com

California has some of the world’s richest and most productive biological carbon (biocarbon) systems. Its forests are global biocarbon champions, and it has some of the most productive, carbon-rich soils worldwide. The state also hosts the largest wetland system of the Pacific in the San Francisco Bay, and wetlands are among the best terrestrial carbon sinks.

But enormous stocks of carbon were lost and released as carbon dioxide with the development of urban areas, conversion of forest to agriculture, and draining of wetlands across the state. The transition from old forests to young ones, as well as that of deep-rooted native grasses to shallow European grasses as dominant vegetation types, has greatly reduced both carbon stocks and annual sequestration.

As part of California’s effort to address global warming, some of the auction revenue from the Cap and Trade program will be invested in our natural resources—from land-use to forest and agriculture programs. Given the interconnectedness of natural systems, PFT is urging the state to create an overarching Biocarbon Plan that takes an integrated approach to these natural resources across all land types and systems.

A blue ribbon panel of external experts and state agency leaders spearheading this effort would help avoid the tendency for each agency to work in isolation, which often leads to missing the synergies, efficiencies, and connections in natural systems.

A Biocarbon Plan would identify goals for increasing biocarbon and methods for restoring and reweaving the state’s biocarbon fabric: from its urban cores to ocean shores and from its working forests to valley agricultural lands. It could also identify how to maximize the climate benefits of restoring biocarbon, be it in reducing energy usage (such as increasing urban shade), increasing renewable energy sources (bioenergy from forest and agriculture waste), improving natural systems resilience (increased species survival), and supporting adaptation benefits (such as watershed health and productivity).

With this overarching plan, the state can make strategic investments and develop policies that take advantage of the power of nature to help slow the rate of climate change, while preparing for the inevitable impacts. Maximizing the benefits of natural systems is the “dark horse” in our fight against climate change. This visionary approach is a key opportunity for California to act as a global innovator and leader.

Donor Profile: Jud Parsons

Donor Profile: Jud Parsons

Fifty years of Forestry, Farming, and Stewardship

Jud Parsons and his wife, Diana Gardner, still own the first piece of land they bought together back in 1959, now protected with a conservation easement. For over 50 years, Jud has managed his extended family’s fruit orchards and forestland near Medford, Oregon, as well as his own forests throughout the state. Today he and his family have begun working with Pacific Forest Trust to conserve their 2,000-acre forest near the slopes of Mt. Ashland.

What do you enjoy most about managing your forest?

I practice sustainable forestry, and do what I can to help lessen the damage in case of a wildfire through fuels reduction. Hopefully they’ll be some income, but also I want to protect the natural resources for water, air quality, wildlife, vegetation, and recreation. The Pacific Crest Trail passes through part of the property that I own and manage; I want the users of the trail to enjoy their experience of walking it.

How did you first learn of PFT?

Back in the early 1990s, Connie Best made a presentation at a Thousand Friends of Oregon meeting, and I was impressed. Now we are working together to draft a conservation easement to protect some of my property.

Why do you give to PFT?

I contribute because I feel the work you’re doing is very important. I’ve visited some of the PFT-conserved lands and I see the value. You want to protect working forests, and you want it done sustainably; I like that philosophy. Oregon has good land use laws, but they’re subject to change. Conservation easements give a higher and more permanent level of protection.