Ensuring lasting benefits in CAL FIRE’s new Forest Health grant program

California’s cap-and-trade program generates revenues for the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund (GGRF) that are reinvested in a wide range of programs to reduce emissions. CAL FIRE has just released draft guidelines for a new Forest Health GGRF grant program that will use some funds from the GGRF for much-needed landscape scale forest conservation and restoration efforts. These projects can increase carbon sequestration and make California’s forests more resilient to climate change – we want to make sure that these benefits last. Read our comments below, or download a PDF, about why GGRF investments in forest landscape programs should endure for at least 50 years.

December 30, 2016

Re: Draft Forest Health GGRF Procedural Guide

Dear Director Pimlott and staff,

Thank you for this opportunity to comment on the CAL FIRE Forest Health GGRF procedural guide (grant guidelines). We appreciate the opportunity to provide feedback and look forward to working together to ensure that the grant guidelines effectively promote lasting landscape scale restoration and conservation. Our recommendations are detailed below, but in brief, we suggest:

- Permanence requirements be updated to reflect budget trailer bill language in SB 859, requiring that benefits persist for at least 50 years,

- Conservation easements associated with these landscape restoration proposals should be decoupled from the Forest Legacy program,

- Coordination with other state departments and plans to maximize synergistic benefits,

- Forest health activities that include burning should be encouraged,

- Advanced payments are necessary for nonprofit participation, and

- Realistic expectations of project size during this first grant round is prudent.

State law requires project benefits to persist for at least 50 years

The GGRF budget trailer bill, SB 859, includes specific requirements for the Forest Health grant program, all of which should be incorporated into the guidelines. Perhaps most importantly, the statute requires grant applications to “include a description of how the proposed project will increase average stem diameter and provide other site-specific improvement to forest complexity, as demonstrated by the expansion of the variety of tree age classes and species persisting for a period of at least 50 years.” Given the many complexities surrounding GHG accounting in a forest context, the Legislature acted to ensure a minimum duration of project benefits and forest structural complexity. Note that in some cases, such as thinning projects that remove significant volume, it may take longer than 50 years to see a net GHG benefit.[1]

While 50 years is the legal minimum, projects that result in permanent changes in management and enduring GHG benefits will provide greater benefit to the climate, are more cost effective over time, and should be prioritized in the project development and selection process. When assessing the value of the changes in management, such as when doing an appraisal, nearly all of the economic impact of the restrictions results from encumbrances in the first 20 years. Because of this “time value of money”, there is little difference in financial impact between a temporary mechanism and securing benefits permanently via a working forest conservation easement. However, the public benefits provided by the later are significantly greater.

A good example of the climate mitigation benefits of a well-designed working forest conservation easement that changes management for climate mitigation and resilience is the recent McCloud Dogwood Butte project with Hancock Timber Resource Management. The terms of the 12,636-acre easement include provisions that increase structural diversity and protect special habitats, amongst other provisions. As a result, the carbon on the property nearly doubles over the next 50 years, sequestering an additional 1.8 million metric tons of CO2. That is the equivalent of taking 380,000 cars off of the road – for a price of $6.50 ton.

Conservation easements associated with these landscape restoration proposals should be decoupled from the Forest Legacy program

Forest Legacy is an important program that has done much for conservation in California, and PFT supports its continued use. However, it is not the right mechanism for easements implemented as part of the landscape projects being contemplated under the Forest Health program. The slow process of reviewing and ranking Forest Legacy proposals is incompatible with the aggressive timeline for the Forest Health program.

The new Forest Health program will be selecting projects based on a variety of factors such as threats and readiness. Conservation easements may be used to secure the improved conditions and maintain the public benefits of the investment, but those easements will be developed in conjunction with, and as an integral part of, the Forest Health proposal. The use and terms of easements should be at the discretion of the Department and the Director, developed in coordination with the Department of Fish and Wildlife.

Coordination with other Departments and state plans increases synergistic benefits

These landscape-scale projects have the potential to advance state goals for carbon sequestration, water security, wildlife adaptation to climate change, and sustainable biomass energy. As such, the coordination between this grant program and other state efforts including Safeguarding California and the Water Action Plan should be maximized. For instance, the eighth grant requirement on page 25 which is currently “Local Fire Plan or Other Forest Management Plan Compatibility” should be expanded to “Compatibility with State Plans” to encompasses the broader range of plans discussed above.

In other sections, the guidelines could be altered to give higher priority to projects that increase the ability of wildlife to adapt to climate change. This includes prioritizing projects that provide critical habitat linkages and/or improved habitat quality. Rather than simply assuming that all forest projects provide wildlife habitat, the grant should explicitly encourage projects that increase linkages and improve habitat, especially for threatened and endangered species.

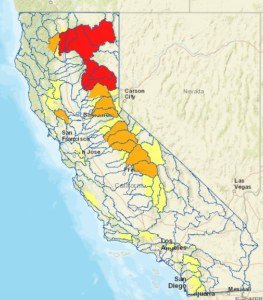

Figure 1: Priority areas for California’s surface water storage from the 2010 FRAP Priority Landscape Viewer.

The potential benefits to watersheds from this grant program are discussed throughout the grant description. FRAP’s Priority Landscape Viewer can be a useful tool to identify watersheds of critical importance to the state’s surface water storage (see Figure 1). Using this map-based tool for prioritization could help improve the synergy between this grant program and other state documents such as the Water Action Plan.

Finally, we recommend that project selection and the refinement of details such as fuel reduction prescriptions and conservation easement terms include participation from other departments, similar to the THP review team process. In addition to DFW (and other review team agencies as appropriate), coordination with other departments will help facilitate awareness of other efforts and create opportunities for synergistic activities. This should include the Natural Resource Agency staff for grant programs such as the Environmental Enhancement and Mitigation Program and the Wildlife Conservation Board which has a great deal of knowledge about other potential or pending projects.

Forest health activities that include burning should be encouraged

In light of the Prescribed Fire MOU and the scientific consensus that California’s forests need more fire, not less,[2],[3] activities that encourage the use of prescribed fire should be encouraged in the Forest Health program. Fire is an essential ecological process that generates more habitat diversity, and restoring mixed severity fires can reduce the high severity fires which can have significant impacts on water quality and carbon stores. We suggest that additional weight is given to projects that focus on restoring fire to the landscape by using prescribed fires or managed natural burns either alone or in combination with other fuels reduction treatments.

Advanced payments are necessary for nonprofit participation

Running multi-million dollar grants as reimbursements is going to be an obstacle for many non-profit organizations that are otherwise well-positioned to implement this program. We were heartened to see the note on page ten that advances could be authorized for nonprofits and we encourage the Department to work with NGO partners to make advances available as efficiently as possible.

Clarification of project size would be useful

While we are supportive of “thinking big” and addressing issues at scale, we urge the Department to start with modest projects in this first year, especially considering the March 2020 deadline for the current round of funding. Much smaller projects are likely to be more realistic to develop and implement in this timeframe, and future years can bring the projects to a larger scale. In the near term, it is important to demonstrate that the Department can deliver successful projects and that this program merits further GGRF investment. That will be easier to do on projects of 10-20,000 acres, rather than 750,000 or a million acres.

Thank you for considering these comments. Please don’t hesitate to call if you have any questions, or if we can be of assistance in any way.

Sincerely,

Paul Mason

V.P. Policy

[1] Loudermilk, E.L., R.M. Scheller. P.J. Weisberg, A.M. Kretchun. 2016. Bending the carbon curve: fire management for carbon resilience under climate change. Landscape Ecology

[2] Marlon, J.R., Bartlein, P.J., Gavin, D.G., Long, C.J., Anderson, R.S., Briles, C.E., Brown, K.J., Colombaroli, D., Hallett, D.J., Power, M.J., Scharf, E.A., Walsh, M.K., 2012. Long-term perspective on wildfires in the western USA. PNAS 109, E535–E543. doi:10.1073/pnas.1112839109

[3] Calkin, D.E., Thompson, M.P., Finney, M.A., 2015. Negative consequences of positive feedbacks in US wildfire management. Forest Ecosystems 2, 9. doi:10.1186/s40663-015-0033-8